A Tale of Two Storms

By AdministratorChances are, you read a lot about Hurricane Harvey when it transformed Houston, TX into a disaster zone in 2017. 68 people were directly killed from Harvey's devastation, 30,000 displaced, and 1,000 homes completely destroyed.

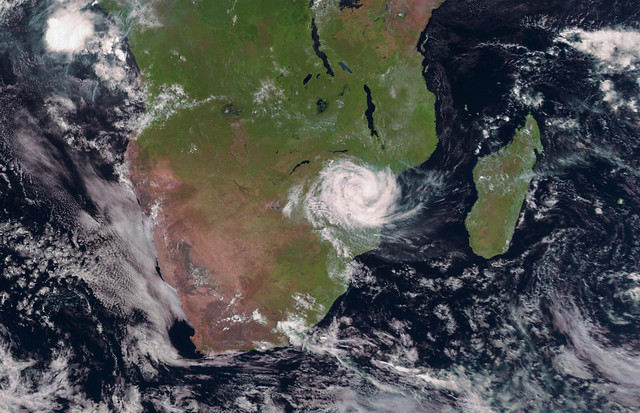

This spring, disasters of even greater magnitude laid waste to Eastern Africa. In March, tropical Cyclone Idai— one of the worst on record to affect the Southern Hemisphere— slammed Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Malawi. It destroyed the port city of Beira, submerged entire villages and 700,000 hectares of crops. It killed more than 1,000 people, misplacing thousands more.

This devastation was immediately followed last week by Cyclone Kenneth, striking the Comoros and Northern Mozambique. Over 160,000 additional people have been displaced by Kenneth, 30,000 houses destroyed, and 24,000 people estimated to need shelter. 38 are confirmed killed.

Despite the significantly higher human cost of the past two month's disasters, chances are that those of us in the U.S. heard non-stop about Harvey while it happened, and have so far heard comparatively little of the cyclones. Why is this?

Researchers have found that in American media, a high death count does not necessarily translate into more intensive journalistic attention. This is unfortunate, as the the success of humanitarian responses to these disasters— including philanthropic campaigns like ours— is often swayed heavily by media perception.

What informs these decisions?

Current research and expert opinion propose a few factors:

-

Proximity: the event’s geographic proximity to the reader.

-

Local protagonists: is there a local person involved in the disaster which can simplify the crisis for an audience?

-

Is there a human antagonist? The presence of a human threat— like a shooter or terrorist— may trigger a biologically higher state of alert in an audience than a natural disaster. It also inflicts a heightened desire to memorialize the victims.

-

Children: the presence of children can often bridge psychological gulfs between audiences and victims typically created by distance, class, race, and nationality.

-

"Newsworthiness”: journalists impose their subjective analysis of how well a story will perform, taking into account factors like the victims' notoriety or the story's novelty.

-

Societal commentary: A human killer, for example, may cause us to reflect on the societal causes of his tragedy. A natural disaster, however, may simply be regarded as an "act of God."

-

"Collapse of compassion": high death tolls numb audiences to important stories. Humans naturally tend to feel less compassion for groups than for individuals.

The bottom line: when it comes to human beings, the path to empathy runs naturally through our filter of whether we can personalize a story.

This makes emotional sympathy a problematic moral tool: it urges us to care most about those with whom we most easily empathize. Evidence shows this is often the people who look most like us, whom we find most attractive and least threatening. We are not naturally predisposed to care most about the people who most deserve it.

FBB as a philanthropic organization often struggles with these factors. In addition, human beings are inclined to want concrete evidence of the impact of their altruism.

"For example," says FBB Programs Director Wendy Webber, "adopting a child to pay their school fees and books are often successful and campaigns. In reality, we know that it's more effective to implement programs that have a larger impact on the entire school community. However, it's a hard sell for donors because the impacts of those programs are largely long-term and seen in statistics."

The good news is that humans aren’t just emotional animals; we have the unique ability to reason. We can use empathy to spark us into action, and temper it with reason and personal practice to generate the more useful psychological tool of compassion.

While it’s inevitable that our hearts will respond more strongly to a disaster nearer to us, we have the ability to still our minds and react to humanitarian crises according to their actual need.

As we engage in supporting secular disaster recovery efforts in Mozambique (alongside our partners with All Hands and Hearts), we call on our followers to reflect on our shared responsibility: expanding our sense of compassion beyond our immediate emotional reactions, and getting into action, whether we're serving those next door or half a world away.