Diversity in Discourse: Challenging Linguistic Imperialism

By Joelle ClayborneLanguage is more than a mere tool for communication—it shapes our identity, carries our cultural heritage, and reflects our understanding of the world. The intricate dynamics of language and power manifest in many ways across societies, particularly through phenomena such as language colonization and linguistic imperialism. Understanding these concepts is crucial for appreciating the complex interplay between language, identity, and power.

Unpacking Language Colonization and Imperialism

Language colonization and language imperialism are two concepts that both deal with the dominance of one language over others, but they are used in slightly different contexts.

Language colonization is a phenomenon wherein the dominant language, typically associated with a colonial or economically superior power, marginalizes or replaces the native languages of a particular region or community. Often, this process is accompanied by a sense of superiority associated with the dominant language, perceived as the only valid mode of communication, intellectual discourse, and cultural representation.

Language Imperialism goes beyond the historical context of colonization. It is a form of cultural imperialism and refers to the dominance of one language (often English in today’s world) as a global standard. It doesn’t necessarily involve a colonizing power and colonized people, but rather the establishment of a language as dominant or superior in global commerce, academia, internet, media, etc. The concept of language imperialism is often associated with Robert Phillipson’s work, who argues that the spread of English globally is a form of linguistic and cultural imperialism (Phillipson, 1992).

Historically, the genesis of modern Western academia can be traced back to medieval European universities, where the curriculum and instructional methods were predominantly influenced by Aristotelian philosophy and Christian theology. During the colonial era, the knowledge systems and cultures of indigenous peoples were frequently dismissed as primitive and inferior, often perpetuating a Eurocentric bias that undermined non-European knowledge systems and perspectives.

The Detrimental Impact

Language imperialism leaves behind a trail of cultural erosion, loss of diversity, and identity dilution. As native languages wane, they carry along a wealth of cultural knowledge, memories, traditions, and stories. This cultural attrition is not merely an individual or communal loss, but a lamentable reduction in humanity’s collective heritage.

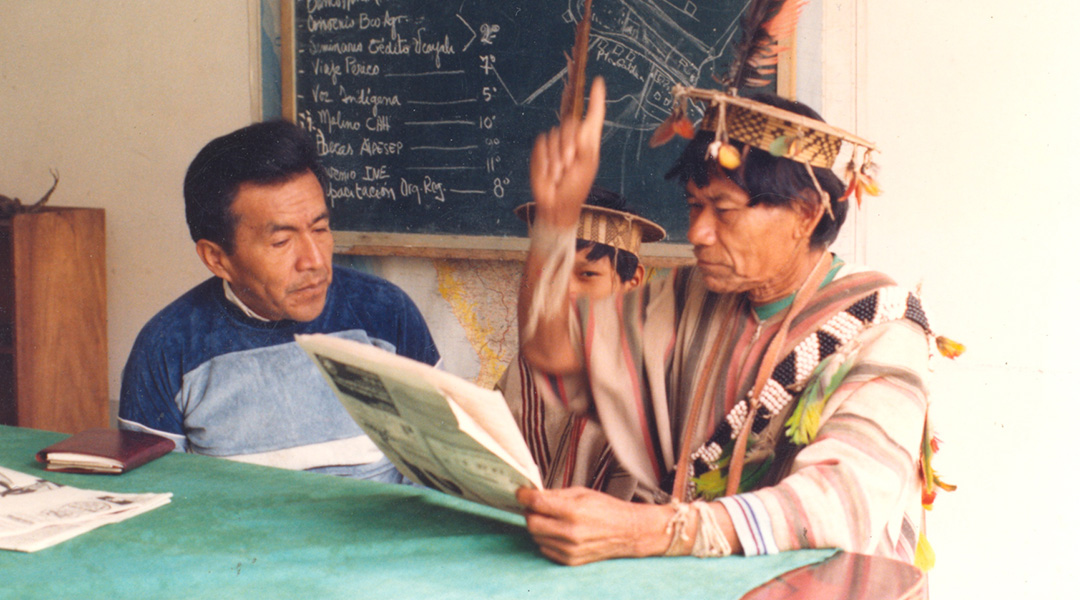

Photo: iwgia.org

Additionally, the oppression of diverse languages and vernaculars leads to a deficit of diversity in literature and other cultural expressions. With the extinction of languages comes the disappearance of the unique literary, artistic, and cultural expressions they nurtured. This cultural homogenization limits our understanding of the human experience and undermines the potential for cross-cultural dialogue and learning.

As renowned postcolonial scholar Spivak intriguingly suggests, “language, in its capacity as a symbol of independent identity, inevitably weaves itself into the fabric of literature, myths, and traditions” (Spivak, 1990). In her view, colonial powers, both past and present, utilize language as a tool to project their culture, presenting it as a modern and superior entity, while simultaneously devaluing and disintegrating the cultural identities of subjugated nations.

Structural and Publication Biases

Language imperialism fosters structural biases that often permeate academic and research institutions, resulting in a systemic marginalization of diverse voices. A pervasive Eurocentric perspective influences hiring, promotion, and tenure decisions, leading to a significant underrepresentation of individuals from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. This bias not only narrows the scope of scholarly discourse but also results in a reduced exploration of diverse cultural knowledge systems and intellectual traditions.

The publishing industry is likewise tainted by these biases. The preference for research and content that aligns with established paradigms and methodologies often sidelines works that feature diverse voices and perspectives. This marginalization extends to authors who employ vernaculars and non-dominant languages, whose valuable contributions are frequently overlooked in favor of content in more widely spoken or academically accepted languages.

Publication bias is not confined to academic writing; it also has profound implications for the media industry. While there is a growing recognition of the need for more diverse voices, the requirements imposed by media platforms often prove to be exclusionary. The insistence on Associated Press (AP) or other formal styles can be a barrier for thought-leaders who lack formal training in academic writing or who prefer to express their ideas in their native vernaculars. Moreover, the editing process can sometimes strip the content of its cultural nuances, resulting in a homogenized narrative that is stripped of its original cultural context.

Contemporary Examples

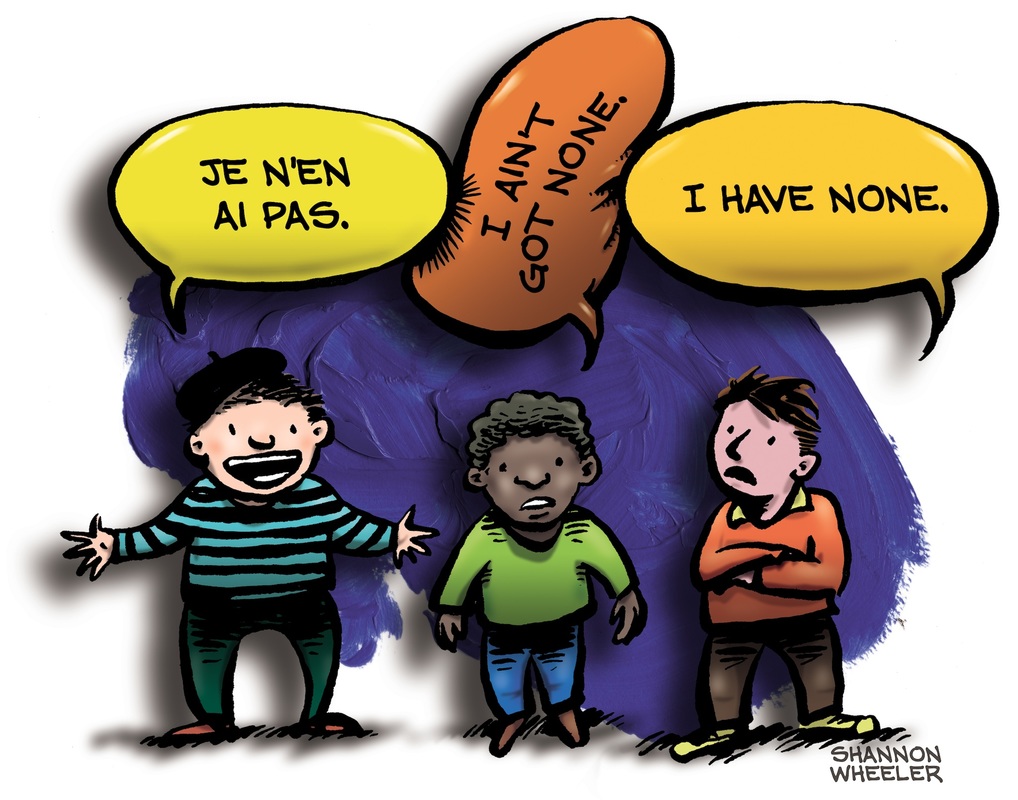

A significant example of language imperialism today is the pervasiveness of English in global discourse. Historically colonized and economically powerful, English has established itself as the de facto lingua franca in international relations, business, science, and the digital world. This dominance often marginalizes non-English speakers and overlooks other languages and their associated cultures.

For instance, African American Vernacular English (AAVE), a dialect distinct to certain African American communities, often faces stigmatization and is considered “less correct” than Standard American English. This bias neglects the rich linguistic and cultural history embodied in AAVE, perpetuating linguistic inequality and contributing to cultural erasure.

On the other hand, language colonization is evident in the suppression of indigenous languages in post-colonial nations. In many African countries, for example, colonial languages like English, French, or Portuguese often eclipse indigenous languages in education, media, and governmental affairs, which is a lingering effect of the colonial past.

Similarly, One contemporary example that sparks discussions and debates within the Latinx community is the use of gender-inclusive language. The terms “Latinx” and “Latine” have emerged as alternatives to traditional gendered identifiers such as “Latino” or “Latina.” While some individuals and organizations embrace these inclusive terms as a way to challenge and dismantle gender norms, others view them as unnecessary or even imposing Western notions of gender onto a language with grammatical gender distinctions. The debate surrounding the use of “Latinx” versus “Latine” reflects a broader conversation about the complexities of language, culture, and identity, and raises questions about the influence of linguistic imperialism on gender inclusivity within the Latinx community.

These instances reflect the complex, ongoing challenges of linguistic diversity and equity in today’s interconnected world. They underscore the need for a more inclusive and respectful approach to language use, where each dialect and vernacular is recognized and valued for its unique contribution to human cultural diversity.

Charting the Way Forward

In the face of these challenges, theories like critical race theory and womanist theory have emerged as vital disciplines that seek to highlight the experiences and perspectives of marginalized groups. These theories challenge conventional narratives, offering fresh lenses to examine structural inequalities in academia and society at large.

Language colonization is a deeply ingrained issue with roots in historical power dynamics. However, the growing awareness of its detrimental effects and concerted efforts to counteract them provide a beacon of hope. This includes institutional support for language revitalization programs, dismantling biases in academia and publishing, and fostering an environment that cherishes linguistic and cultural diversity.

Language colonization is a deeply ingrained issue with roots in historical power dynamics. However, the growing awareness of its detrimental effects and concerted efforts to counteract them provide a beacon of hope. This includes institutional support for language revitalization programs, dismantling biases in academia and publishing, and fostering an environment that cherishes linguistic and cultural diversity.

In an increasingly interconnected world, the importance of amplifying diverse voices cannot be overstated. By breaking free from the confines of culturally, and linguistically oppressive notions, we can enrich our collective discourse and foster a more inclusive, empathetic, and diverse global community. This will not only celebrate the unique cultural tapestry of our world but also ensure that the richness of human expression is duly recognized and preserved. After all, in the words of anthropologist Wade Davis, “The world in which you were born is just one model of reality. Other cultures are not failed attempts at being you; they are unique manifestations of the human spirit” (Wade, 1997).

GO Humanity: Our Commitment to Linguistic Diversity

As we navigate the ramifications of language colonization and imperialism, we at GO Humanity are steadfast in our commitment to counter this trend and champion linguistic diversity. We recognize the richness that diverse voices, literary styles, and vernaculars bring to our collective discourse, and we’re dedicated to fostering a platform that celebrates this diversity.

We firmly believe in the transformative power of diverse voices. We understand that the rigid constraints of dominant languages and formal writing styles can often suppress authentic expression and exclude those who may lack formal academic training. To remedy this, we are actively striving to break these boundaries and provide a space where diverse voices are heard, respected, and valued.

We firmly believe in the transformative power of diverse voices. We understand that the rigid constraints of dominant languages and formal writing styles can often suppress authentic expression and exclude those who may lack formal academic training. To remedy this, we are actively striving to break these boundaries and provide a space where diverse voices are heard, respected, and valued.

Moreover, we acknowledge the power of literary style as a form of cultural expression. We know that every culture has a unique way of telling their stories, and these individual styles add richness and depth to our understanding of the world. By welcoming a variety of literary styles, we aim to disrupt the homogeneity often found in mainstream media, creating a vibrant, diverse literary landscape.

A book drive held by GO Team HAPI, benefiting locals in the Philippines

Perhaps most importantly, we appreciate the value of vernacular languages. We understand that these languages are more than just means of communication; they are vessels of cultural identity and knowledge, offering a unique lens through which we can understand and appreciate different cultures. Therefore, we are eager to highlight and honor these vernacular languages in our future blog posts.

In our ongoing commitment to this cause, going forward, you can expect to see more blog posts on GO Humanity featuring diverse voices, embracing a variety of literary styles, and honoring vernaculars from around the world. We believe that by doing so, we can contribute to a more inclusive, understanding, and richly diverse global discourse.

GO Humanity is more than just a platform for sharing diverse voices; we are a movement dedicated to challenging oppression, and bigotry while celebrating the richness of global cultures. We aim to amplify marginalized voices, honor diversity, and in doing so, play our part in resisting language oppression and fostering a more inclusive and respectful global discourse.

Joelle Clayborne is a Diversity, Equity & Inclusion consultant, success coach, and dedicated advocate for anti-racism and racial equity.

References

Annamalai, E. (2001). Managing Multilingualism in India: Political and Linguistic Manifestations. Sage Publications.

Baugh, J. (2000). Beyond Ebonics: Linguistic Pride and Racial Prejudice. Oxford University Press.

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a Global Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Davis, W. (2009). The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World. House of Anansi Press.

Hornberger, N. (ed.) (2008). Can Schools Save Indigenous Languages? Policy and Practice on Four Continents. Palgrave Macmillan.

María Del Río-González A. (2021). To Latinx or Not to Latinx: A Question of Gender Inclusivity Versus Gender Neutrality. American journal of public health, 111(6), 1018–1021. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306238

Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic Imperialism. Oxford University Press.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2000). Linguistic Genocide in Education–or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights? Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Spivak, G. (1990). The Post-Colonial Critic: Interviews, Strategies, Dialogues. Routledge.

#LinguisticImperialism #LanguageColonization #CulturalDiversity #LanguageRights #VernacularLanguages #InclusiveDiscourse #LinguisticEquality #LanguageRevitalization #DiverseVoices #GlobalLanguage #LanguageJustice #LanguageRights #IdentityAndLanguage #LanguageBias #DecolonizingLanguage