Marry Me: Gender Roles and Assumptions in Ghana

By AdministratorI can’t count the number of marriage proposals I’ve received since moving to Ghana. I 've also had a number of people ask me to give them my camera when I have it out and am taking pictures. Our cross-cultural training instructor told us that these requests for our belongings are both a joke and serious. They don’t expect you to give them the item. But if you do, score! I have been told repeatedly by many different Ghanaians, including our cross-cultural training instructor, that the marriage proposals are also a joke. A way to keep the conversation going. I suspect, however, that a similar dynamic exists as with the camera. They don’t expect me to say yes, but they’ll certainly take a sillimiinga (literally “white man”) wife if I do.

But it doesn’t feel like a joke. Not after we’ve circled back to the original question a fourth, fifth, or sixth time. It feels serious because they don’t let it drop. They ask, I say something funny (or at least try to, humor is can be so hard cross-culturally), and they ask again. Repeat. It’s exhausting.

To be fair, there is a language barrier too. The repetition of the question may simply be because they think I don’t understand what they are asking. Or my answers simply don’t make sense. One tactic some sillimiingas use to answer that they are married whether they are or not. Some go so far as to wear fake wedding bands. I choose to tell them the truth. No, I’m not married. No, I will not marry you. I’m not looking to get married at all. There is an assumption that a woman must want marriage and babies. The idea that a woman would get to my age and not accomplish marriage and babies–and is okay with that–does not compute.

Our cross-cultural training instructor told us that “woman” has two definitions in Ghana: wife and sister. (I didn’t think to ask at the time why mother wasn’t included.) Though calling women “my sister” or just “sister” is quite common, I am not these men’s blood sister. I guess that leaves wife.

At the heart of the exchange, and my reaction to it, is a question of how much to play by the rules of another culture when those rules deeply offend your own values. I am not in Ghana as anthropologist committed to observation. Nor am I here to force American values on a culture that is not mine. On the other hand, being told, repeatedly, that my value–my personal value as a human being–has no more dimensions than marriage and babies and, furthermore, that my life is not mine to direct is not easy. Accepting that assumption does not sit well with me.

It is emotionally wearing to have the same conversation again and again and again no matter what the content. If that content is dehumanizing, it is more difficult to laugh it off. As satisfying as flipping the table and storming off would be, I don’t think that would actually do much except widen the gap between us. When I enter every encounter with a new man in Ghana braced for the likely possibility that this conversation will come, that gap is pretty wide already.

At the very least, my answers to the questions challenge their assumptions about women’s rights. I am in Ghana to support a women’s rights organization after all. No, I am not married. No, I do not have any current plans to marry. No, I do not have babies. I’m okay with that. Know who else is okay with that? My parents. My parents and my society.

It’s delicate, but I have to find a balance–the balance between challenging culturally held beliefs that are different from my own and engaging a culture on its own terms. All the while not letting the dehumanizing conversations leave a mark on me. I have not found that balance yet. But I’m working on it.

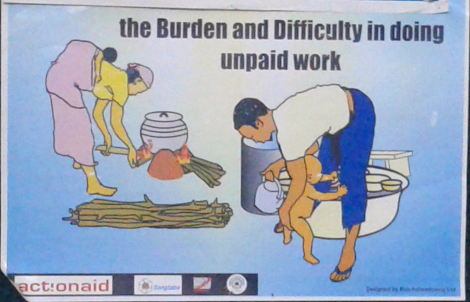

Image: A sign at the office of our partner organization, Songtaba. Gender roles in Ghana remain very rigid, especially in the rural Northern Region.