“More to be done by human hands”—Alix Jules

By Administrator Diversity isn’t an abstraction to Alix Jules. He was raised by a single mother and grandmother in a section of Brooklyn he calls a “mini UN Assembly—mostly Afro-Caribbean,” where one island’s music was often systematically drowned out by another, and “the smell of jerk chicken clashed with the distinct hint of New York sewer.”

Diversity isn’t an abstraction to Alix Jules. He was raised by a single mother and grandmother in a section of Brooklyn he calls a “mini UN Assembly—mostly Afro-Caribbean,” where one island’s music was often systematically drowned out by another, and “the smell of jerk chicken clashed with the distinct hint of New York sewer.”

His committed Catholic family went to church several times a week. “The church represented hope, love, salvation, forgiveness, and family for me then. My family was big—but this was bigger. I had no father in my life, so my heavenly father, who sacrificed his other son for my sins—was an amazing substitute! That was love. To this inner city kid who felt rejected by his own father, that was very powerful. And there was no way my grandmother could be wrong.”

Well into his teens, Alix had his sights set on the priesthood. “I saw the good that my priest did in alleviating suffering. It was very real. He took pain away. He made people happy when they got married. He kept people together when they hit rock bottom and when addiction was crippling, he gave them a real hand and even more—hope. In the ghetto, hope is good. It was needed. Not many make it out without it.”

He was exposed to diverse beliefs and cultures at a specialized high school in the Bronx. “I met my first Buddhists and my first Muslims who weren’t affiliated with the Nation of Islam. I got to know them, like them, and more importantly, understand them.”

It was here that he also met his first nonbelievers. “I made it a point to get into debates with them. I wanted to prove them wrong. But the more I studied to strengthen my arguments, the more I undid those arguments. I got to a point where I gave up studying religion out of fear. I adopted Islam for a few months, then returned to Catholicism and even enrolled for a short time in seminary. But I came to realize that I didn’t just have problems with religion, but with deities and their morals. I declared myself a scholarly ‘Agnostic’ in my twenties, still not ready to cross that line.”

As it did for countless others, September 11th pushed Alix over that line. “I could not believe in a deity that would allow that to happen in his name. I was pretty much done. Never again the Eucharist. Never again to whisper to the wind in the hopes that something that would do nothing to intervene for thousands would ever do anything for me.”

Alix was living in Texas by this time, but returned to New York as quickly as he could after the attack. “I walked the streets, searching, and saw hope erased from faces where no amount of prayer could ever repair the despair. Just providing a human shoulder to cry on or sharing a moment of pain with someone did more than I ever could have had I worn a collar, trying to justify it all as part of some divine plan. There was more to be done by human hands in undoing what was done by human hands.”

As he began to engage more directly with the freethought community, Alix began to see both a problem and opportunity in the relative lack of diversity. “Different can be difficult for any organism. We live separately and are not always incented to cross into the other side. We find disproportionate amounts of suffering with the non-privileged and undervalued classes in society, yet we ignore them. It’s the status quo. Education is also undervalued there, but we do little to change it. We have people who want to help on both sides but don’t always know how. The problem of race exists regardless of belief system. If we confront, rather than ignore, and at least begin to examine critically how we do things—then it’s my hope that we can build actionable plans and humanist bridges.”

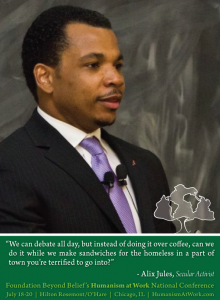

The key is turning existing values into action. “We talk about education constantly in the freethought community—so we should be lining up to give it away! How about a little bit of prep for a college interview or a first job for a kid that never knew he had a future? If we did that, we’d be helping to provide a special kind of different—a new kind of hope to those who see no use in dreaming. It would also increase diversity within the freethought community faster than a billboard, because minorities measure what you do rather than what you say. We can debate all day, but instead of doing it over coffee, can we do it while we make sandwiches for the homeless in a part of town you’re terrified to go into? Can we do it while we organize a book drive in a neighborhood you normally speed through? Can we do it while we mentor and tutor those inner city youth who make you lock your car doors TWICE?”

Alix is optimistic about the direction of the movement, though he says further strides are needed in diversity, gender, outreach, and volunteering. “I’m really optimistic that we’ve organized to the point where we have a sustainable charitable foundation. That’s massive. It gives us an option to collectively pool, leverage, and be heard. We also get to do good. The Pathfinders Project also excites me to no end, and I’d love to see more programs like that sprout in other organizations.”

More than anything, Alix says, we have to get our hands in the game, not just our money. “People should donate, because programs require funding. But many people trade their money for their time, and many local organizations suffer not from lack of funding, but lack of volunteering. We need more people helping and more hands doing.”

See Alix Jules at the Humanism at Work conference, July 18-20 in Chicago. Register now!